Psychedelic Literalism: Part Two

In which we critique McKenna's Gnosticism, perennialism, and the myth of a primordial psychedelic experience.

This is part two of of five in a series on psychedelic literalism and the ways we interpret non-ordinary states of consciousness.

McKenna and the Tease of Immediacy

“Language is not an indirect method of communication, to be contrasted with ‘direct’ thought reading. Thought-reading could only take place through the interpretation of symbols and so would be on the same level as language. It would not get rid of the symbolic process.”

—Ludwig Wittgenstein

Two things before we begin our exploration of Terrence Mckenna’s philosophical assumptions. First, I want to say that I find his soliloquies thrillingly inventive. Even if his views fail to cohere into the kind of durable spiritual perspective I’m always on the lookout for, he kept things going during the psychedelic dark ages of the 80s and 90s, exhibiting a curiosity and cognitive agility that defined for so many what it meant to be a psychedelic explorer.

Second, given how frequently McKenna quoted Heidegger, he should have known better.

Several months ago, I was preparing to facilitate a book group on McKenna’s True Hallucinations. To get into the spirit of McKenna’s wild Sci-Fi-adjacent journey into the Amazon, I listened to a number of talks, including this one, recorded at Esalen in March, 1996, in which McKenna posits a polarity between “nature” and “culture.”

Here are his remarks:

The only time you recover the natural state of human beings is in orgasm and in psychedelic apotheosis. And then, you know, for fleeting moments you recover it. Then you’re dropped back down through levels and levels of culture, programming, obligation, matrix stuff, matrix, matrix. Anyway, what I wanted to get to is how to do this, how to get out of culture, how to get out of three-dimensional space, how to get into this superspace. Well there are two main methods on the table, and one is through—no matter how you cut it—some manipulation of the body… And strangely enough often unaccompanied by substance, plants or drugs, but almost always accompanied by enormous doses of fuzzy thought and ideology, usually known as religion. So there is that path. And the claim that you can achieve somehow the paradox of being outside, without ever leaving culture, by using the cultural instrument of religion to religion to make your way to the heart of the mystery, I reject this. I just think it is bunk. It is an effort to close the loophole. It is an effort to channel spiritual thirst that is still culturally affirming. But spiritual thirst can’t be culturally affirming, because it is a rejection of culture. Culture generates spiritual thirst. Okay, so the other method on the table are psychedelics.

Isn’t this interesting? The goal, McKenna states explicitly, is to get outside of culture. “Radical human freedom is what you were born for,” he says in the same talk, “and culture is a kind of placenta, which if you develop normally by around age twenty you have no need of it.”

To be clear, by “culture,” McKenna is not talking about stinky cheeses and erudite conversations during intercession at the Met. Nor is he talking about culture in the broad sense of mainstream Western culture. By culture, he seems to mean any collective social context in which meaning-making happens.

Not “a” culture, but culture as such.

All these remarks are met without challenge from his audience. In fact, people begin asking him how to do it. And McKenna has an answer. Again and again in his talks, his psychedelic theology becomes praxis in the exhortation to take “five dry grams in silent darkness.” It’s a clear line from a philosophy of culture-escape to this minimalism. Isolate yourself. Withdraw the mind from the senses. Clear away the clutter of language, imagery, environment, and get closer to the “real thing.” “Avoid gurus, follow plants,” goes another famous McKenna quote. Direct, unmediated Gnosis: this is the proper psychedelic initiation.1

A nice sentiment. But doesn’t it overlook something vital and, well, inevitable? Doesn’t it, by ignoring the decisive role of socio-cultural contexts, enter into a delusion that communication—whether it be from humans or plants—could ever take place through some kind of direct, cultureless vector?

What we’re dealing with here, if you haven’t already caught on, is a sneaky version of psychedelic literalism.

*

Let’s pause and remind ourselves what our school of Continental Philosophy observes about experience.

You are always inside a “tradition.”

A tradition is a set of pre-ontological understandings that constitute our relationship and comportment to being.

This relationship influences what “shows up” in your Lebenswelt and is the precondition for personal experience.

In sum, our being in the world is situated within and forestructured by a tradition. There is no place “outside” tradition from which to think or represent experience. We do not live in the Unconditioned Formlessness; where we live, all there is is one big interpretive space.

The Tease of Immediacy: this is how Continental philosophers might describe the wriggly hope of making lasting contact with “reality as such” outside of mediating factors. Sucking off layers of interpretation is indeed possible; tricky, but possible. But to actually arrive at full-on Immediacy? To grasp it in a way that can be formalized and represented—in short, made constitutive of a philosophy?

Nah.

All Immediacy is embedded in Mediation. Moments of so-called direct experience take place within and are shaped by our contexts and traditions and stories. It is not possible to fully and permanently separate culture and nature, self and world, interpretation and reality. You can pull the poles apart, but they will always snap back.

(Yes, all Mediation is also embedded in Immediacy—neither is master, neither has the upper hand. But our purposes are are to correct overzealous literalisms.)

What, then, do we do with McKenna? Immediacy seems to be his prize hen. It become a whole spiel in another talk: “What life… is supposed to be about is the reclamation of the primacy of direct experience.” But there is a big ol’ blind spot in this view. By positing a kind of a-cultural gnosis, a perspective “outside culture,” and then by claiming this perspective, he renders himself—in the same way as that non-denominational pastor who “needed no hermeneutic”—immune to critique.

One example is all we need. So here is Graham St. John, in his cultural history of DMT, describing McKenna’s take of shamanism:

Expressing the view that the hyperdimensional experience is “too numinous and energy-laden to be accessible through a tradition,” McKenna held that the gnosis should not be governed by administrators of the divine, but “must be personally discovered in the depths of the psychedelically intoxicated soul.” … The possibility of direct, unmediated gnosis was declared to be a human right, an idea striking appeal among his audience.2

Catch that? McKenna is making it out as though it’s only the shamans who have traditions. Not him. He’s the one free of cultural and theological baggage.3

He isn’t alone in this, either. The feeling of possessing unmediated knowledge, a knowing that needs no external validation, is not uncommon in psychedelic states. It can even alter entire worldviews, as this study suggests.

Now, personally, I believe there are indeed ways of using these compounds that make us more self-aware about our cultural assumptions. Psychedelics may indeed alleviate what neuroscientists call “canalisation” (i.e. “over-learning”) and as a result temporarily free us from ingrained patterns of relating to ourselves and the world. Psychedelics may even help us realize the deep dependence of our experience on presuppositions and reality frameworks.

However. It’s different when you think you’ve “arrived” at something.

The danger of McKenna’s language is the danger present in all traditions that claim privileged access to unmediated truth. We know how this goes. History is full of confident middle-aged men who think they’ve arrived at the metaphysical pinnacle. Here’s Caputo again, getting snarky:

What we always get—it never fails—in the name of the Unmediated is someone’s highly mediated Absolute: their Jealous Jahweh, their righteous Allah, their infallible church, their absolute Geist that inevitably speaks German... Somehow this absolutely absolute always ends up with a particular attachment to some historical, natural language, a particular nation, a particular religion.4

*

In case you’re getting worried, I promise I’m not leading you towards nihilistic relativism. This isn’t some cynical post-modern take-down of earnest quests for truth. Such a quest is what we’re on right now. (Do you have your vorpal blade?)

What we are examining is the dichotomy between “culture” and “experience” and the attempt to abstract the former form the latter. To pursue this naively is to be a sucker for the “Tease of Immediacy”: the always-beyond-ness of direct experience which resists formalization and representation. Psychedelics, it seems, can give energy to this wild goose chase. They can engender a yearning for a naïve realism that abdicates its interpretive responsibility in co-creating the reality it lives into.

There is a far more popular and innocuous-seeming version of this. You know it as…

Perennial Philosophy

“There is no mysticism as such, there is only the mysticism of a particular religious system, Christian, Islamic, Jewish mysticism, and so on.”

—Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism

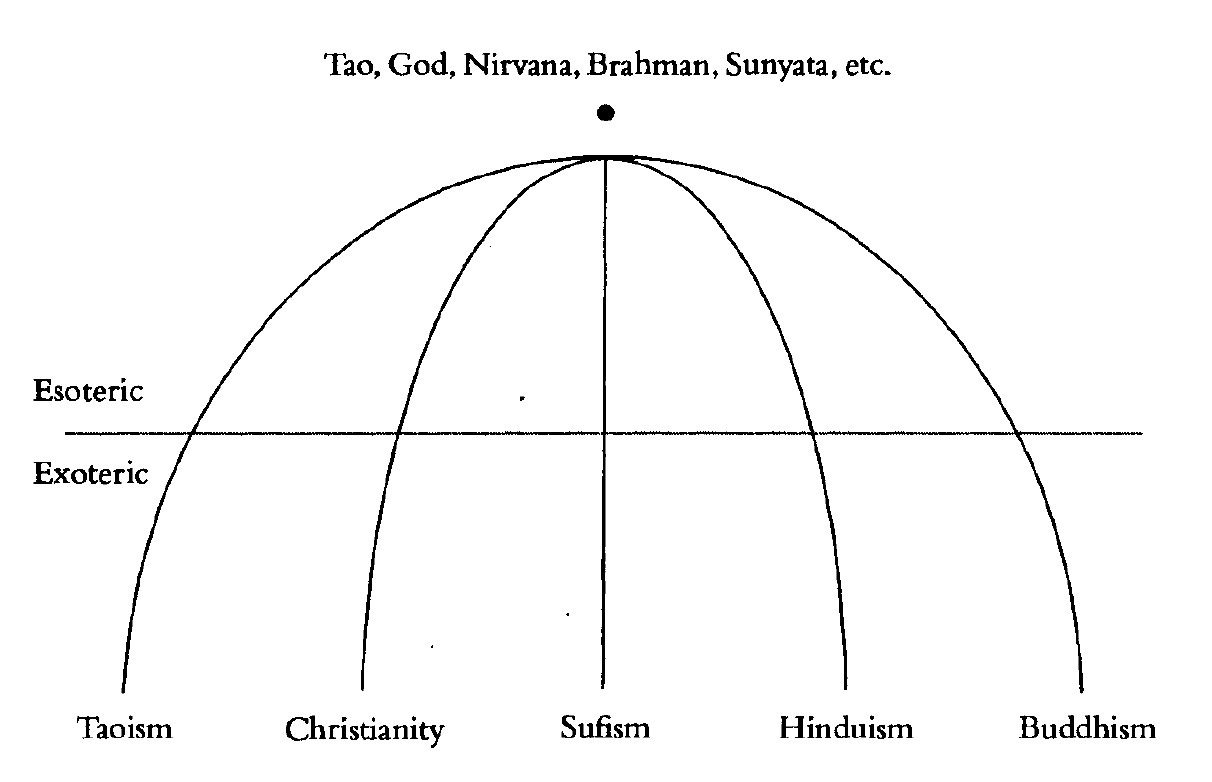

Perennial philosophy refers to the notion that all religions share a common mystical core and as such are expressions of the same Divine Truth. In other words: when you undress each tradition of its language, its stories and texts, its mediating factors, you find the same naked body.

You can see where this is going.

But let’s give some hermeneutical charity to the perennialists. Philosophia perennis has a longstanding history, dating back to its first coinage in 1540 by Agostino Steuco, and arguably further still, into the Neoplatonism of the 3rd century. It is, in part, an effort to respond to an urgent existential problem resulting from the various truth claims across the world’s spiritual traditions. How do we account for such a rich and conflicting visions? Who is “right”? The perennialist answer is to cut right through so-called superficial differences and posit a nameless, wordless, unmediated knowingness behind it all in which everyone can participate. Advaita Vedantists call it Brahman, Taoists call it the Tao, Christians call it union with God, a practitioner of Patañjali’s yoga call it asamprajñata samadhi, Sufis call it Allah, Kabbalists call it Kether, Zen Buddhists call it sunyata. But “it’s all the same thing.”

Perennial philosophy enjoyed a surge in popularity in the 20th century, in part thanks to Aldous Huxley. Many psychedelic thinkers and researchers now hold this perspective.

Dr. William Richards, for example—one of the leads in the Johns Hopkins clinical trials. He uses this very perennialist language to conclude his book:

God awaits and embraces us both as Ground of Being (Celestial Buddha Fields, Pure Land, The Void that contains all Reality, The Ground Luminosity of Pure Awareness) and as Personal Deity (Lord Jehovah, Lord Jesus, Lord Krishna, Lord Buddha).5

You can also see Dr. Anthony Bossis, the director for a clinical trial at NYU on the effects of psilocybin on religious professionals, quoting perennialist Abraham Maslow during his presentation at the MAPS conference Psychedelic Science 2023: “All religions are the same in their essence and have always been the same.”

And Stan Grof himself, a friend of Maslow’s and a figure whose influence is hard to underemphasize in the field of psychedelic research and transpersonal psychology, states of his research: “It became clear that I had rediscovered what Aldous Huxley called ‘perennial philosophy.’”6 He even wrote a whole book on the theme: The Cosmic Game.7

The claim made by these psychedelic researchers is, in short, that the psychedelic experience participates in the same mystical core that perennial philosophy posits across religions.

But here’s the problem. And you know what I’m going to say next—so I’m going to have Jules Evans say it: “The idea that psychedelics predictably lead to a unitive experience beyond time, space and culture is itself culture-bound—it’s the product of US culture, and the perennialism of Huxley, Dass, Ralph Waldo Emerson and others.”8

I want to be careful here. This is subtle territory. It’s worthwhile to draw comparisons and see patterns where they exist across cultures, across traditions, and across individual experience.9 These psychedelic researchers, and perennialists in general, are responding to and interpreting a very real “data set”: mystical texts and experiences. They are, you might say, looking for a “unified theory of consciousness.”

But recall Gadamar’s insistence on the universality of hermeneutics. Recall our critique of McKenna’s Gnosticism. What we want to avoid is the creation of a wholly new tradition that, blind to the hermeneutical process, becomes hubristically invisible to itself as an interpretive tradition.

And that seems to be what’s happening here.

There’s no getting around it: perennialism is an a priori philosophical stance. A likeable stance, certainly. But full of bias. It favors a nondual monistic metaphysic, values commonality above difference, and tends towards objectivism by claiming a universal underlying structure of consciousness and reality. As a consequence, it becomes quietly dogmatic. It insists, in one way or another, on a single ultimate spiritual realization.

In his book, Rational Mysticism, John Horgan interviews a delightfully scornful anti-perennialist named Steven Katz, who has this to say about that:

There is no universal mystical truth apprehended by Christians, Jews, Buddhists, and Hindus alike; mystical experiences are enormously diverse, and they invariably reflect each mystic’s particular culture and personality.

Or, as Katz puts it more bluntly elsewhere, “There are NO pure (i.e., unmediated) experiences.”

Katz goes too far, in my opinion. Yes, the conceptual/metaphorical/mythological containers of each religion are more powerful and ontologically decisive than perennialists acknowledge. But zealous postmodernists have a way of overemphasizing the power of context and thereby, in my estimation, undermining the possibility of transcending our particular cultures and traditions. It’s a self-fulfilling (self-damning) prophecy.

All the same, let’s receive Katz’ corrective. Putting it our own words: all experience, even mystical knowingness, is embedded in a larger context of mediation.

This is the reason that religious traditions shape different spiritual characters. It’s the reason mystical states themselves differ. As Jorge Ferrer points out, “The more precisely mystical states are described, the more disparate they appear to be.” See, for example, Jess Hollenback’s research on the contextuality of mysticism.10 When you look at how it gets expressed, the values it suggests, its personal and social ramifications, etc., the nondual experience of a Vaishnavite in the 12th century just flat-out unfolds differently than the ecstatic devotional experience of a 16th Century Benedictine monk.

The container is not absolutely determinative, of course, but it is inescapably influential. Just as with psychedelic trips.

Which brings us to…

The Myth of a Primordial Psychedelic Experience

“The whole point of these psilocybin interventions, [Dr. Anthony Bossis] concedes, is to trigger the same beatific vision that was reported at Eleusis for millennia.”

—Brian C. Muraresku, The Immortality Key

So, we have (a) the idea that all religions, when you look past their particulars, share a common originary mystical experience; and (b) the idea that psychedelics can occasion that same experience. What happens when you bring them together, and add a pinch of conspiratorial thinking?

You get… Brian C. Muraresku.

Muraresku’s recent book, The Immortality Key, is responsible for re-hypping an old hypothesis first posed by John M. Allegro in 1970’s The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. Allegro’s idea was admittedly a little more farfetched. He argued that Christianity had its origins in mushroom cults that survived into the current era. Muraresku’s version relies on ergot fungus in the kykeon wine mixture from the Greek mystery cults. It comes to the same thing in the end, though: psychedelics are responsible.11

What was the original sacrament of Western civilization? And did it somehow sneak its way into the primitive rites of Christianity? If the experts ever turn up new information on the real reason why the universe of Greek-speaking pagans became the founding generations of Christianity, turning a Jewish healer from Galilee into the most famous human being who ever lived, it promises the Reformation to end all Reformations. Because the mystical core, the ecstatic source and true lifeblood of the biggest religion the world has ever known, will have finally been exposed.12

For all the pizzaz and salesmanship, there is actually a solid scholarly argument here. I don’t quite buy it, others do—I’m not going to get into that. I’m more interested in the assumptions that motivate Muraresku’s research and frame its importance. The assumption, namely, that inserting psychedelics as “causal factors” in religious and philosophical systems changes something fundamental about our understanding of those systems, and human history itself.

It’s a Gnostic claim, basically. There is a secret, a “final” revelation, hidden behind the revelation.

And it’s drugs!

(I’m imagining the conniption fits all this would induce in Karl Barth, a theologian who scorned the demythologization projects so fashionable among the European intelligentsia of his time. The revelation, the spiritual catalyst—oh, it couldn’t possibly have anything to do with the claim that God became flesh and dwelt among us! Simply unpalatable!)

I do understand why this is an important hypothesis. If it’s truly a buried history, it matters. Especially in our current context of the war on drugs, religious prejudice, injustice and ongoing stigma.

But, looked at hermeneutically, it misses the point. From Anthony Wallace’s 1959 paper, “Cultural Determinants of Response to Hallucinatory Experience,” through to today’s millionth psychedelic newsletter, “set and setting” have been long acknowledged as factors equally important as the psychedelic catalyst. But Muraresku (a psychedelic virgin by his own admission) writes as though he’s never cracked Double Blind Magazine.

What made Eleusis special wasn’t the sacrament. As Joshua Schrei of the inimitable podcast, The Emerald, says:

Imagine years of waiting to be initiated. Friends who have gone through the initiation and come back changed but can’t speak about it. What little they say comes with the welling of tears, tears that arrive with the memory of something sharp and bright. Whispers of the story of the goddess to be told in full only at the festival. One’s entire socio-cultural experience of the world oriented around this mythic narrative of death and renewal.

In other words, the secret of Eleusis isn’t a secret, it’s right there on the surface. It’s not the ergot fungus in the kykeon;13 it is every element of the rite.

It’s the fasting.

The dancing.

The all-night vigil inside the Telesterion.

The presence of the holy Anaktoron, which only the hierphants could enter.

It is the whole ritual complex which, moving the initiates through mythologized action inside a container so sacred that to divulge its contents meant death, culminates in a peak experience of participatory awe.

No part of that isn’t sacred: that is the secret.

*

So Muraresku downplays the importance of the container. Why is that so concerning? Because behind it all broods that same Gnostic craving we saw in McKenna. Get outside the symbols. Escape culture, see the Truth. That’s what it’s all about, man.

Here’s Muraresku once more, and it’s only page thirty-six: “Back in the Garden of Eden, maybe the forbidden fruit was forbidden for a reason. Who needs the fancy building, the priest and all the rest of it—even the Bible—if all you really need is the fruit?”

Can you hear it now?

We don’t need no hermeneutic. All we need is the fruit.

By ignoring the power of symbols and myth, by ignoring the role of interpretation and the contextual web of meaning, we lose sight of what makes these experiences meaningful in the first place.

Erik Davis, a historian of the weird, cleverly observes the latent irony:

The desire within the psychedelic community to reduce the rich and highly variegated phenomena of religious experience to secret psychoactive cults is, I think, misguided and historically problematic, at least given the associational and fantastic way that most people try to pursue it… Such literalism actually goes against one of the main features of psychedelic experience and psychedelic cognition, which is that the world, whatever else it is, is profoundly metaphoric. Our experience is not literal; the world is not literal. And yet people want to discover a literal drug at the heart of religious experience to reduce the latter to the former, just like good skeptics.

In short, those who lean on psychedelics to explain religion in fact lose the mystery for a newfound materialism. If you think you understand Eleusis because a scholar tells you there was probably a lysergamide somewhere in all that fasting and kerfuffle, and if as a result you think that you can reproduce Eleusis in some session room at Johns Hopkins with a dose of psilocybin…

Well, I don’t know what to tell you.

But this assumption can reach even deeper levels of ridiculousness. Jules Evans, writing about New Age and neo-shamanic churches making up their own religions, relates this anecdote from MAPS’ Psychedelic Science 2023 conference:

At the panel to present the initial findings of the Johns Hopkins / NYU ‘psychedelics for priests’ study, one man stood up in the Q&A and said: ‘I run a psychedelic church with a congregation of over a 1000, we’re also training around 80 ministers. Any advice on what sort of cosmology we should have?’

There was a long pause. ‘That’s totally out of my wheel house’, replied Roland Griffiths.

I got chills reading this. Chills. The mythology, the story, the values—they’re an after-thought! Not even a particularly important after-thought if they can be asked about during a panel Q+A. What does this church leader think myth is? A generic plug and play item? Pick a myth, any myth will do! I mean, are you serious right now!? *Throws laptop across room*

This is a rejection of our own hermeneutical freedom. You could even say it is a rejection of meaning itself. It is life denying. As though the particular nature of the story the church tells, the values it embodies, the mysteries it points to, could be dealt with the way we settle a bill…

But we’ll return to this point later. We’ve got more literalist territory to cover.

*

Fun fact. John Lilly’s use of ketamine and LSD in sensory deprivation tanks would also seem to be an extension of this philosophy. In fact, his inspiration has a very different source, beginning as an effort to test the hypothesis that the brain would shut down when deprived of sensory input.

Graham St. John, Mystery School in Hyperspace: A Cultural History of DMT (2015).

McKenna makes the same claim again with the term entheogen. Graham St. John: “There are parallels here with what Jonathan Ott has identified as the Entheogenic Reformation, even though McKenna himself balked at using the term ‘entheogen,’ which he thought ‘a clumsy word freighted with theological baggage.’” …As though “psychedelic” doesn’t also have cultural and theological baggage.

John D. Caputo, “How to Avoid Speaking of God: The Violence of Natural Theology,” in Prospects for Natural Theology, ed. Eugene Thomas Long (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1992), 129–30.

William A. Richards, Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experience (2015).

Christina Grof, Stanislav Grof, The Stormy Search for the Self: A Guide to Personal Growth through Transformational Crisis (1992).

“This research... shows that, in its farther reaches, the psyche of each of us is essentially commensurate with all of existence and ultimately identical with the cosmic creative principle itself. This conclusion . . . is in far-reaching agreement with the image of reality found in the great spiritual and mystical traditions of the world, which the Anglo-American writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley referred to as the "perennial philosophy.” (Stanislav Grof, The Cosmic Game: Explorations of the Frontiers of Human Consciousness, 1998, p. 3)

Jules Evans, “Caves all the way down.” We could add Ken Wilber to the list.

As Federico Campagna points out in Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality: “As argued in recent decades by the Japanese philosopher and historian of religions Toshihiko Izutsu, as well as by thinkers in the Perennialist tradition, it is possible to trace an uninterrupted meta-philosophical debate on the metaphysics of the ineffable, that crosses the geopolitical barriers between the East and the West, while orbiting around the area of the Mediterranean Sea as its symbolic ‘centre’.”

Or if you’re interested in the differences between mystical states and spiritual characters within the tradition of Christianity, see one of my favorite books, Ways of Imperfection.

The idea of a sacrament reserved for the priestly class of the ‘old religion’ is itself old and had popularity in pre-war Europe. See Alan Piper’s essay, “Leo Perutz and the Mystery of St Peter's Snow” in Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture.

Brian C. Muraresku, The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion With No Name (2020).

The kykeon is a barley drink that first had to be shaken to be imbibed, to keep all its ingredients evenly distributed. The speculation is that one of its ingredients was ergot fungus, which grows on barley and contains alkaloids similar to LSD.

Fun fact: when I was twenty, I wanted to tattoo the Greek word κυκεὼν on my leg. I’d discovered a footnote in a Robert Graves book that mentioned the theory above, and having done mushrooms twice by that point, I thought that was pretty dope. Then, reading Heraclitus, I came across these two fragments. They became for me a gnomic meditation on profoundest being, a koan hinting at paradoxes beyond paradoxes.

(83) It rests by changing.

(84) Even the kykeon separates if it is not stirred.

κυκεὼν is the only tattoo I’ve ever wanted, aside from a Basho haiku. (I know, I know.) I’m glad I dilly-dallied; I could not have suspected how lame the psychedelic renaissance would make that tattoo in just over ten years.