Psychedelic Literalism: Part One

In which we define hermeneutics and psychedelic literalism.

Introduction: Nostalgia for Truth

his mirror broken a thousand times

frightened

listening

not wanting to be lost

drawing plans

of the plans drawing themselves in him

—Henri Michaux

Two summers ago, I smoked a bowl of cannabis and found myself coming up on DMT.

Surprise!

I’d known there might be DMT residue in the pipe from past sessions, but it took me three deep drags to realize I’d drastically underestimated the amount. Part of me was thrilled. How many chances do you get to trip without expecting to? The other part neared panic. At the time, I was cat sitting in Connecticut. Holding that last hit in my lungs, I lay on the lawn and stared up at the backyard’s massive elm as a sentient-seeming warpzone opened in and around me. The leaves transmuted into hieroglyphs, my body into an expanding plane of energy. Each second I held it took me higher.

I could go as high as I like, I realized, just by keeping it in my lungs. When to stop? How to make such an increasingly important decision with such a decreasingly functional mind?

I exhaled—but the transdimensional membrane kept peeling back. Feeling radically undefended, I stumbled into the house, stretched out on the sofa, and there, frantically choosing a comforting song on my phone, glided into a full-on DMT-inflected cannabis journey.

*

Why do I tell this story? First, to make clear that as the self-serious concepts stack up in what follows, I’m really just a goof who accidentally doses himself with superpotent psychoactive molecules.

Second, because of what happened next.

In those first ten minutes, the challenge of self-stabilization presented itself as cosmically important, even—oh, psychedelics—somehow fractally or synecdochely related to a more significant and longer-term spiritual process. Was I “spiritually prepared” for this, I wondered? Abraham Heschel, a Jewish theologian, describes the goal of the religious path as a readiness to face holy moments.1 Holiness, being holiness, is beholden to nothing. How, then, did one become the kind of person who could meet the unannounced in-breaking of the sacred with the gravity and poise it required?

…Such as when you accidently smoke DMT? (Forgive me, Heschel.)

There was no getting around it: I had to be my own guide. Despite having set no intentions and prepared no container, I had to make meaning of the trip in real time, sorting myself out from within the mess of my own thoughts while simultaneously coming to grips with the very related and discomfiting intuition that this imperfect coping-through-the-mess, this authority-less space through which I tumbled, is actually the way things are for everyone, across all spiritual traditions, at all times, period.

Oh, psychedelics.

It was a moment that seemed to bring together the whole history of my eclectic spirituality. Since high school, my world has been rocked by countless great hearts—Thomas Merton, St. Augustine, Theresa of Avila, Angelus Silesius, Shantideva, Ram Dass, Hafez, Ibn Arabi. The hunt for ever more exotic, ever more cosmologically and mythically novel teachings and practices has driven me into some strange and magical corners of the library. But behind this search, it seemed to me—suddenly, on that Connecticut couch—I had, all along, been looking for something that doesn’t exist: a ruler, a perfect “straight edge,” an absolute and authoritative reference point against which to grow.

Sometimes I turn on a tape recorder while tripping. It helps with recall later. Plus, those slurred utterances, in all their dorky and over-earnest energy, often become goofy little koans to unpack.

I did so now. A surprising heartache erupted in me as I spoke, so deep and heavy that it felt like missing a loved one.

I have this yearning for a complete teaching. Something that is really truly complete. But because of who we are, there can’t be a master text. There can’t be.

Everything is just improvised.

An idol was crumbling away, a vestige of a spiritual naiveté that, though I knew better, I had unconsciously taken comfort in. Indulged, as Castaneda’s Don Juan might say. I know that all wisdom teachings have a situated history. But I hadn’t let myself feel the depth of what that meant. Tantra, Vipassana meditation, Sufi whirling, Hesychasm, Cantillation—every spiritual practice was ultimately born out of and remains characterized by the same messy reality in which I found myself now.

There I was, yearning for an Ultimate Tradition. A Master Text. A sure and guaranteed path to walk down. Yearning, in other words, to escape context, situatedness, and the whole hermeneutic process.

Ha!

*

In this piece, I will explore how similar yearnings play out in the world of psychedelics through what I’m calling—bundling together a diverse but unified set of subcultural phenomena—psychedelic literalism.

This will be more of a ramble than a treatise: I can’t hope to make definitive arguments on a topic so nuanced and quantum-unstable, nor do I want to. I’d rather presume your first-hand knowledge of psychedelics, as well as a baseline level of readerly patience and interpretive charity. We’ll get into the juicier stuff that way.

I will touch on:

Forgive me if this occasionally feels polemical. My true hope is that readers will receive these reflections as an invitation into a deeper participation with the psychedelic phenomenon and the freedom it can open up.

What is Literalism?

“Revelation does not reach us in a neutral state.”

—Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics

Imagine a world in which no one ever dreamt. There, that sui generis oneiric reality we all know, in which anything can happen and every emotion is available to be felt, simply doesn’t exist. People just go to sleep and wake up.

Now imagine that for the first time in this world, someone… dreams. They wake up and recall a bewildering, utterly improbable sequences of events that, furthermore, seemed to have happened differently than things usually happen.

What is this person to think? How are they to talk about it? How assign value, significance, or indeed reality to the occurrence?

Without any cultural context to guide them, things could go nearly any direction.

Imagine, now, others beginning to dream. Soon thousands and tens of thousands have their own stories. People are waking up confused, excited, heartbroken. It’s making the news. Someone has a wet dream, someone has a blood-curdling nightmare. Someone insists they’ve seen the future. Dream coaches enter the market. Peer support circles form. The first book on dreams is published, and now dream virgins want an experience too. Theories abound on Tik Tok: it’s a parallel dimension, it’s a message from your higher self, it’s random neurons firing. Someone claims to have found the key to dream symbols and offers readings for $333. Rolling Stone Magazine publishes an article about Amazonian tribes who have been dreaming for thousands of years…

Sound familiar? We’re living this story now.

*

The use of psychedelic substances is exploding in North America. According to this Monitoring the Future study, it quadrupled among 35-50-year-olds over the last decade, and tripled among 19-30-year-olds last year. Judging by the number of drug dealers now spamming my zero-posts Instagram account, I’d say this checks out.

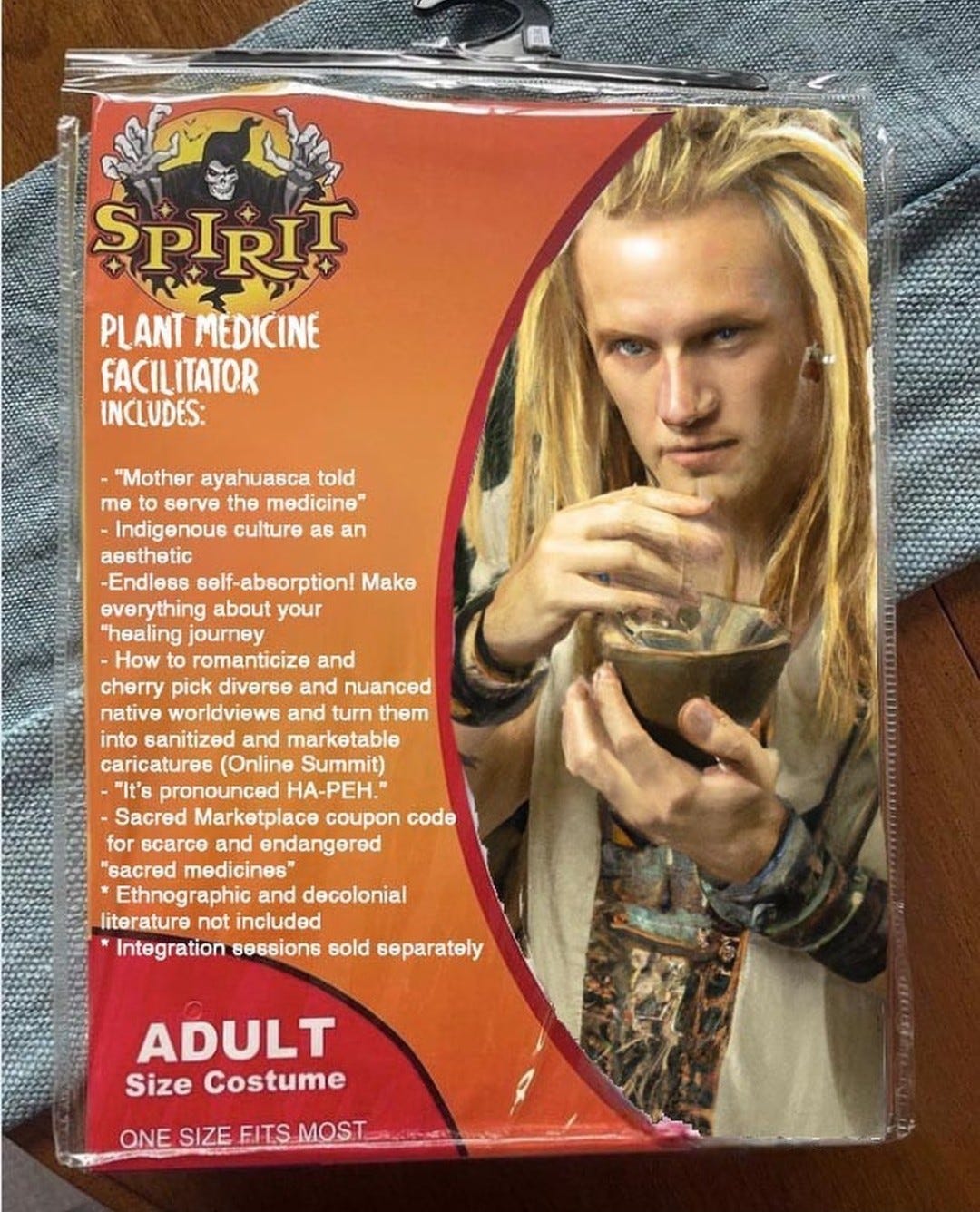

Simultaneously, psychedelic subcultures are crystallizing. As someone involved in the psychedelic “field” since 2021 (what has the “field” come to that I can’t type it without quotes?) I’ve had a front row seat to it all. We’ve got the trauma-heads over here, the hard-core DMTx psychonauts clamoring to be the next hyperspace Columbus over there. We’ve got the feel-good neoshamans, the microdose moms, the earnest therapists, the VC bros on the scent for the next burgeoning market. It’s a subculture in itself to mock the subcultures: thank you Adam Aronovich and Dennis Walker.

But while engagement with psychedelics increases, ecstatic literacy lags behind.

A term coined by Jules Evan, ecstatic literacy refers to the way we make sense of ecstatic experiences, including psychedelic states. Currently, there is no lack of intellectual engagement with psychedelics per se. But when we speak about our trips, how aware are we of the presuppositions, values and models that inform our meaning-making? Are we holding these experiences with critical and historical awareness? There are, of course, plenty of thinkers who model this to an advanced degree.2 But on the whole, the tone out there in psychedelia is still mostly hype-filled and pseudo-intellectual. People are under-resourced to process their experiences through robust critical frameworks.

And it shows. In this qualitative study on ayahuasca drinkers, Alex Gearin found that a “resistance towards ascribing metaphorical status to psychedelic experiences” was “shared by many ayahuasca drinkers in the United States, Europe, Australia, and elsewhere… For some, marking a psychedelic vision a metaphor is an ontological offense akin to treating a sober memory like it was a fairy tale or fiction.”

I get it. To call such powerful experiences “metaphorical” might feel like a diminishment.

But isn’t this backwards?

Isn’t this, rather, a drastic underestimation of the power, and indeed of the reality, of metaphor?

Don’t get me wrong: it’s wonderful that more people are learning to clear trauma from their nervous systems, grow fluent in the somatics of emotion, re-access bodily pleasure, unleash primal energy at consciousness festivals, etc. But if the mission is to “mainstream” psychedelics, to spiritualize humanity and democratize mystical experience, and if hundreds of thousands, even millions, of people are going to be pursing the drug-induced ecstasies that movers and shakers like Bob Jesse tell us are our “birthright,” then, unless we want to lock ourselves into new broken stories, we need more sophisticated and self-critical frameworks than literalism.

*

Time for a definition? “Literalism,” in philosophy and theology, generally refers to any way of conceptualizing or speaking about texts that does not recognize the foundational role of interpretation and context in shaping the message of the text itself.

Take Christian fundamentalism, for example. I’m not just talking about Westboro Baptists yelling in the streets. My Dad, an Anglican priest, has this telling story from his seminary years involving a non-denominational pastor. They were chatting about sermon writing. For background, it is standard for pastors and priests, when preparing a homily, to use a study Bible to supplement their knowledge of Hebrew and Koine Greek, plus dozens of commentaries which provide book-by-book exegetical support.

“Oh, I don’t use any of that,” the pastor said.

“Then how do you do exegesis?”

“We just read the text. We don’t need a hermeneutic.”

My Dad was appalled. At the time, I didn’t fully understand my Dad’s reaction; now those words make me shiver.

We don’t need a hermeneutic.

The ancient Greek word hermeneuein means “to utter, to explain, to translate.” A hermeneutic, then, is a way of interpreting. You can’t not have a hermeneutic. Would you read Breitbart News with distrust or credulity? That’s a hermeneutic. Would you read First Corinthians as addressing a particular minority community in an oppressive empire two thousand years in the past, or as a message intended for you, now, as you scroll BibleGateway your phone? That’s a hermeneutic. You can study history through a hermeneutic of suspicion (Nietszsche, Marx, Freud), a hermeneutic of charity (Augustine, Kierkegaard), or even a hermeneutic that treats everything as a kind of endless aesthetic play (Derrida, Borges, yay!).

And if you think you don’t have a hermeneutic, then, buddy, your hermeneutic is unconscious. And remember what Jung said about that:

Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.3

Just look at the disturbing spectacle of the mega church: hundreds of thousands of people engaging with an ancient collection of texts as though nothing were required to understand their messages but a sincere heart—nay, the feeling of a sincere heart. In reality, it’s confirmation bias in overdrive: cherry-picking questionably translated New Testament passages to support homophobia, fear of female leadership, revenge-fantasies, and the almost literal worship of Moloch (capital). And you can’t even argue with them, because they won’t acknowledge their fucking hermeneutic.

So that’s literalism as it plays out in American Christianity. Most major religions have their own version. But what is psychedelic literalism?

This is where things get tricky. Because we’re no longer just talking about interpreting texts, but experience. And what we find when we examine the matter is that experience, and reality itself, has a hermeneutical dimension.

Conception Affects Perception

“The map precedes the territory.”

—Jean Baudrillard

Let’s take a step back and clarify a few key concepts.

When I was a bushy-tailed undergrad, I took a class on Continental Philosophy, a school of thought devoted to examining the non-obvious presuppositions that shape our experience of the world. It is no joke to say it changed my life. Forget illegal drugs: if parents are going to freak out about what their kids get up to at college, let it be over a flirtation with Edmund Husserl.

The basic idea is, well, very basic. So basic it can be hard to grasp. Generally, we position ourselves as observers over against a singular, objective “reality,” and assume that this reality is universally true for everyone at all times. This perspective, it is fair to say, is the default; it’s how most of us operate in the unexamined moments of our lives. It is also the operative scientific stance. Quantum physics notwithstanding, the scientific method presumes to investigate one reality by means of objective measures. Reality as it is “internal to itself,” reality as an object of study, has been the obsession of western philosophers for centuries.

Against this, the Continental tradition operates from the insight that there is no pure, raw, objective experience of the world.

Early in the course, we examined something called the “as-structure” of experience. This is the observation that everything—every object or person or thought or action or Whip-It! charger eyed from across the room—in order to appear to us at all, must appear as something. In other words, sensory experience isn’t an arrival of “raw data” which then gets formulated into this or that. Rather, sensory experience is shaped from the get-go by a set of forestructured understandings, pre-existent categories, values, and expectations: what Husserl calls the life-world (Lebenswelt). For us to experience anything at all, it must manifest according to the shape of this life-world.

As John Caputo writes in our class textbook, Radical Hermeneutics4: “an object is an object for consciousness only inasmuch as consciousness has been motivated to constitute it as such.”

Got it?

Take that Whip-It! charger. When I pay attention to how it shows up in my experience, I realize that I see it right from the beginning as a Whip-It! It doesn’t through a phase transition from an abstract set of lines and curves and colors that I then decide would make a good Whip-It! It is whole—interpreted—from the start. I know pre-cognitively, for example, that it is a thing I could pick up, because I’d be surprised if I found it glued to the counter. I’d be surprised, too, if I went around and found that it had no backside. Or that it smelled tangy. These surprises reveal implicit structural expectations. This is what Caputo means when he says, “The object which is able to appear has been prepared for in advance.” Such predelineation makes my experience of the Whip-It! possible.

Of course, those who don’t know that a Whip-It! contains 8 grams of NO2 and a short-cut to bliss may cycle through various possibilities suggested by that oblong bullet; nonetheless, in so far as they notice it, they will see an “it,” a thing, a meaningful object gestalt. Those who have experienced nitrous addiction, on the other hand, may find the Whip-It! charger has an extraordinary presence in their perceptual continuum. It’s nonvisible “aliveness” draws the gaze… This is interpretation in action. How the Whip-It! shows up for you is influenced by your context, your intentions and expectations, your relationship with it.

So important are these contexts of meaning, these interpretive structures, that it’s fair to say a Whip-It! at a Phish show is a different object than a Whip-It! in a suburban home in which pumpkin pie steams on the kitchen counter.

The point is, interpretation is not just a second-order phenomenon. It doesn’t just happen “after” experience; it is constitutive of experience. It begins before we are conscious of it. To ask for an un-interpreted experience is almost like asking to see matter without form. As Marilyn Robinson observes in Absence of Mind: sensory experience has “the character the mind has given it,” and in this sense, perception functions “as language does, both enabling thought and conforming it in large part to its own context, its own limitations.”

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that it’s “interpretation all the way down,” nor that we can alter reality simply by “interpreting differently.” There is indeed an exterior world, an Otherness. Interpretation does involve a dialectic. But we’ll get to that later. Right now, we are drawing our attention to the deep interpretive structures pre-given by culture and history, by nature, by organisms themselves. These are so pervasive and inescapable that Hans-Georg Gadamer’s titled one of his essays: “The Universality of the Hermeneutical Problem.”

“Language is the fundamental mode of operation of our being-in-the-world,” he claims, “and the all-embracing form of the constitution of the world.”

By “language,” Gadamer doesn’t mean specifically German or English or whatever, but a deeper semantic structure. And by “world,” he means “our” world, our experienced reality, the world that has meaning for us and gives us our basic operational “coordinates.” We could put it this way: language and world, interpretation and experience, are consubstantial. They constitute each other.

In short: all being, insofar as we represent it to others and to ourselves, is mediated by interpretation.

*

I’m asking you to take a lot on trust here, I know. If you’re new to hermeneutics, this is not going to be enough. All I can say is, I promise to do my best to explain as we go. But first, let’s return to our definition in light of the above. What is “psychedelic literalism”?

It is any way of conceptualizing or speaking about psychedelic experience that does not recognize the foundational role of interpretation and context in constituting the experience itself.

You know spiritual bypassing? The use of spiritual ideas or practices to avoid dealing with difficult realities? You might say that psychedelic literalism is a kind of interpretive bypassing.

With that hasty foundation laid, let’s turn at last to the world of psychedelics, and the Bard Terrence McKenna himself.

*

“The higher goal of spiritual living is not to amass a wealth of information, but to face sacred moments” (Abraham Heschel, The Sabbath, page 6).

E.g. Nicholas Langlitz, Neşe Devenot, James L. Kent, Mike Jay, Erika Dyck, Andy Mitchell, the Chacruna Institute, and of course the inimitable Erik Davis.

In an essay on hermeneutics, I feel responsible to point out that Jung may have never said exactly this. See this excellent post about the origins of this famous quote.

John Caputo, Radical Hermeneutics: Repetition, Deconstruction, and the Hermeneutic Project (1987).

Thank you for offering the reference to Jung. Original context not only is important if we want to understand the meaning of an utterance, but it also honors the thinker. I haven’t started publishing yet — but when I do, I’ll keep thar in mind. Carl Jung has become a meme alongside Mary Oliver and Charles Bukowski. Thet could all be the same person at this point. Welcome to the simulacra.