Psychedelic Literalism: Part Three

In which we examine the phenomenology of psychedelic messages and entities, DMT space, and psychedelic ideas.

This is part three of of five in a series on psychedelic literalism and the ways we interpret non-ordinary states of consciousness.

Bro, I’m Getting All These Downloads…

“Mystical states seem to those who experience them to be also states of knowledge. They are states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect.”

—William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience

So far, I’ve outlined how some psychedelic thinkers and researchers have tried to exit the hermeneutic process by abstracting “experience” from “context,” and the path of error they set themselves on as a consequence. I want to talk now about psychedelic experience itself. How do we lose track of the hermeneutic dimension in our own subjectivity?

*

Let’s start with the idea that psychedelics give you messages, most famously suggested in that grating phrase: “If you get the message, hang up the ph—”

*Slams receiver down*

Yup. Got it.

I’ve been so involved in the psychedelic world these last few years that it’s remarkable to recall, now, that I’d been adventuring with psilocybin both privately and with friends for years before I heard anyone talk about receiving “messages” or “learning lessons” from psychedelics. In fact, I remember distinctly the first time I came across that language. Here’s a journal entry from early 2020, after the second or third psychedelic Meetup group I attended in Brooklyn:

Some people talk about using mushrooms and LSD to learn some kind of lesson, like they’re going to an Oracle who has a personal message for them. One guy described learning that he needed to be more of a “leader” in his life. This is great, but it feels reductive. The lessons may be fine, even life-changing, but the “lesson” model is not itself an inbuilt aspect of tripping. And, more to the point, where is the transcendence? Don’t people only receive the lessons they are capable of giving themselves?

I’ve relaxed quite a bit since this journal entry. In fact, I’ve full absorbed this paradigm of lesson-learning as one way of experiencing psychedelics, and have used those same locutions you hear around psychedelic Meetups and integration circles: “LSD taught me such and such.” “The shrooms told me yada yada.” Etc. They are a useful short-hand for a more complex phenomenon that is impractical to detail in every instance. And anyway, I like how those phrases introduce a relational element, framing it as a conversation between me and the fungi, the vine, the toad.

That said, what I sensed in my journal entry holds. Such phrases can also be expressions of literalism.

*

Let’s take for example this common message: “Grandmother Aya told me to spread the word.” I can’t count the number of time’s I’ve encountered this. Richard Doyle, to pull a name out of a hat, describes meeting “a wand wielding bird deity” during a ceremony in the upper Amazon who, after clearing his asthma attack, said: “Look, you know can you write and speak about the fact that you were healed of your lifelong asthma using an ancient Indian technology?”

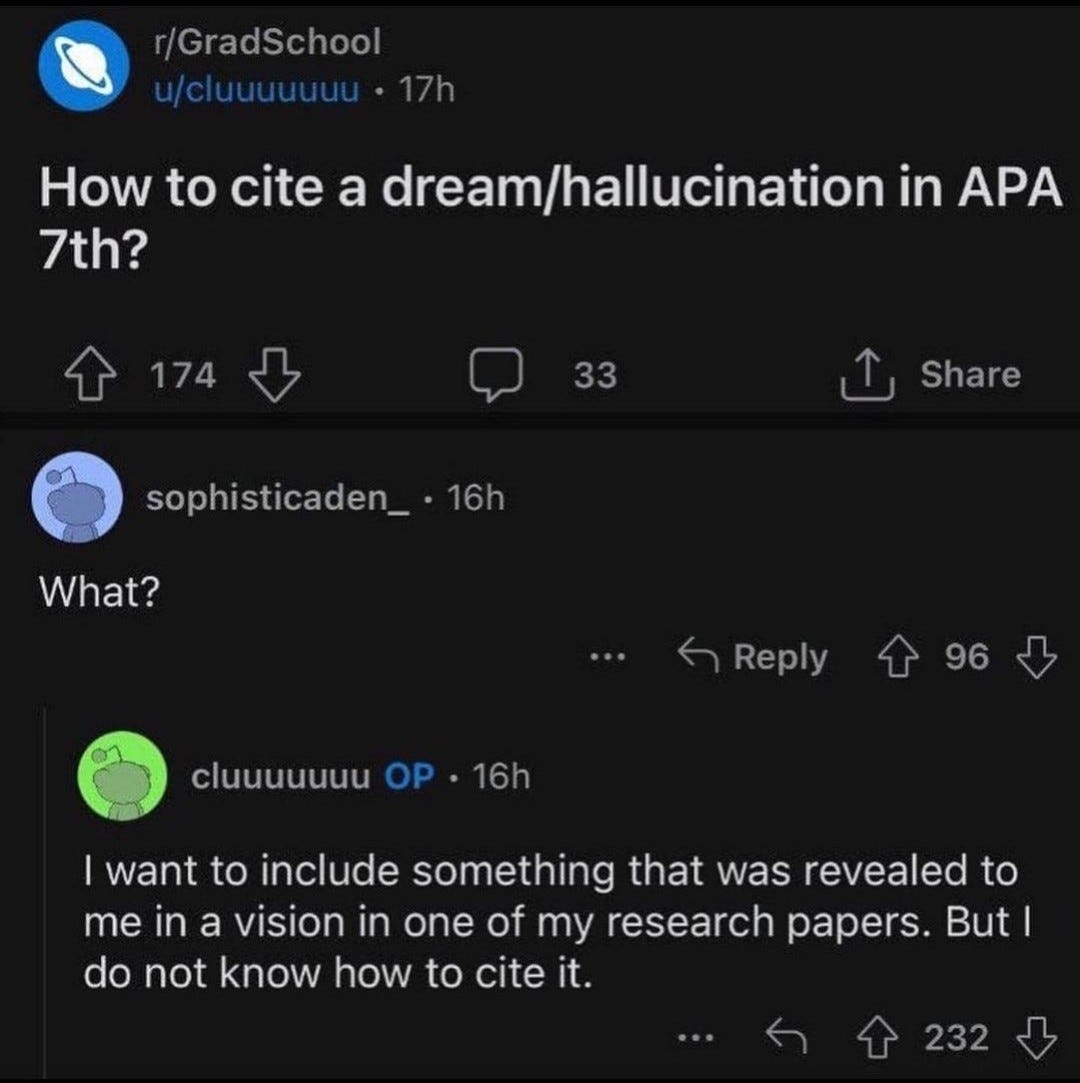

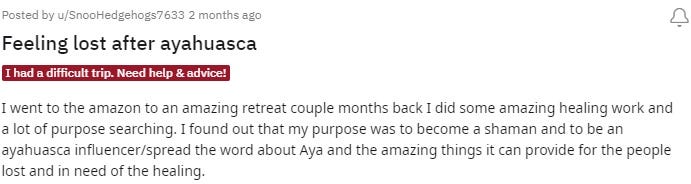

But just dip into psychedelic reddit and you’ll find this sort of thing everywhere:

Jules Evans had something similar happen to him. He describes a snake with a microphone telling him he could become an ayahuasca influencer. “I was naturally flattered,” he writes, “but now I wonder… are the plants / plant-spirits supporting our spiritual growth, or using us as marketing bots?”

There are, then, hermeneutically-hip ways of encountering such “messages,” and hermeneutically-unhip ways.1 Evans shows an awareness of an interpretive dimension that the Reddit poster seems to lack.

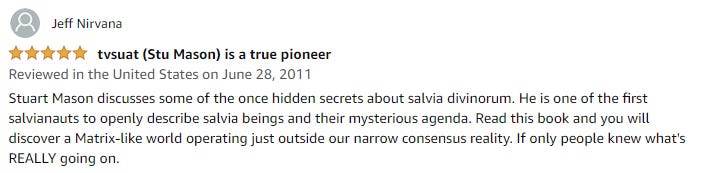

Need more examples? What about this random guy, Stuart Mason, who wrote a book called Salvia Divinorum: Reality of Life and Death? Here’s his description of a 10x salvia extract bong rip that sends him through a hole in the fabric of reality.

A young female, human in appearance… communicated to me that I was about to be let-in on the biggest secret ever. She turned my awareness around to reveal a black curtain, not in my everyday view, but somehow always there, just behind my mind… It was made known to me at this point, that humanity’s history on earth as we had come to believe, was not real. The passing of time was not real.

Stuart goes on to glimpse our universe inside something like a photo booth. He talks with “Light-Beings.” “A lot of knowledge was revealed to me,” he writes.

I don’t doubt it. The trouble is, all this is written with a very straight face. And such a straight face produces straight readings, a literalistic engagement all around—as this Amazon reviewer demonstrates.

Okay, final example. Have you heard of Baba Kilindi Iyi, proponent of the superheroic dose (30-50 dry grams)? “In my travels,” he says, “it was told to me that the mushroom is an organic technology for access to the multiverse memory bank, created to enable one to go into that library.”

I can’t know for sure, but when I hear Iyi talk, I sense little self-awareness of the interpretive choices he is making. He presents himself as a prophet of the mushroom, merely delivering messages the mushrooms gave him.

Now, I’m no super-heroic doser. But I’ve had my share of heroic doses, and whenever I examine the textures of those experiences, whenever I pay very close attention to the dynamics of the visuals and the intuitions and so-called messages in my internal perceptual field, I notice that there is always—always—an active interpretive process and hence an inherent ambiguity. The visuals, the emotions that come up, the bodily sensations: everything is in a feedback loop with my attention. I don’t, for example, see a demon and then feel fear. I see a demon and feel fear at the same time. If I were to try repressing the demon, it might get scarier. If I were to turn toward it, it might get less scary. The demon is not independent of my relationship with it.

In short, psychedelic states are interactive in a way that you can’t “get behind”—the same way you can’t open Schrödinger’s box without influencing the very thing you want to witness (the cat in its non-dual state).

Here’s a journal entry from January 2023, following an ayahuasca ceremony:

I saw a being of unutterable strangeness, a strangeness that wasn’t represented visually so much as the way it utilized representation itself. Picture an immense mushroom cloud which, as it unfurls upwards, arcs toward you, building itself with a pinkish and perfectly polished material. This moving image managed to be two things at once. At no point was it not possible to reduced it to just an interesting visual in my head; at the same time, it had a felt presence, as though another intelligence occupied it, or rather, in a less Docetic metaphor, lived through the image as a finite expression of an infinite reality. The entity, in order to enter my mind, composed itself of the stuff of my mind, but in such a way that it enacted a translucency, a double-vision, allowing me to see at the same time how it was both only a visual and something more.

This is the DMT paradox: something is trying to talk to me, as me.

Psychedelics may indeed lead to encounters with genuine Otherness. But structuring the “messages” that come through, structuring those encounters with Otherness, is always a complicating hermeneutical back-and-forth. This shouldn’t surprise us. It is this way with all experience. Even basic physical sensations are influenced by your way of relating to them, indeed to such an extent that you can’t abstract the sensation from your relationship to the sensation.

Of course I understand the wish that psychedelic messages were “special.” Wouldn’t it be wonderful to access a supreme sage who could somehow bypass the whole hermeneutical process and communicate to us infallible and self-transparent truths? Certainly some trips feel that way. But not even ecstatic feelings are enough to evade the necessity of interpretation.

“NOTHING gets past hermeneutics! Mwahaha!”

—Hans-Georg Gadamer2

This holds true no matter how high a dose of psilocybin you take.

*

One last thing. Literalist interpreters are a dime a dozen on the reddit forums, but there are plenty more nuanced literalisms. We are returning, once again, to McKenna.

In True Hallucinations, Terrence McKenna describes a trip he and his brother took in 1971 to La Chorrera in the Amazon to investigate the “secret” of DMT. It is truly one of the wildest psychedelic tales ever told. Here’s one of McKenna’s run-on speculations that populate the book:

My own reaction to the mushroom’s claims concerning the extraterrestrial origin of tryptamine hallucinogens and the visions that they bear has taken many forms. I think that it is possible that certain of these compounds could be “seeded genes” injected into the planetary ecology eons ago by an automated space-probe arriving here from a civilization somewhere else in the galaxy. Such genes could have been carried along in the genome of a mushroom or some other plant, awaiting only the advent of another intelligence and its discovery of them to begin reading out a message that opens with the bizarre dimension familiar to shamans everywhere... I speculate that the final content of the message will be instructions—it will be called a “discovery”—of how to build a matter-transmitter or some other device that will allow us direct contact with the civilization that sent the message-bearing hallucinogen genes to earth so many aeons ago...

He goes on. But despite the energy of his language, one begins to wonder if it lacks… imagination. Blasphemy, I know. McKenna’s ideas one-up the wildest Philip K. Dyck novels. I mean, to suggest that someone has “seeded intragalactic space with automatic biomechanical probes” which “tailor-make message-bearing hallucinogens for the special ecological conditions…” That’s some Deep SF right there.

And yet.

What does it amount to but simply: we are receiving messages from aliens?3

I’m not saying this isn’t a possibility. I don’t even mean to imply that it’s silly or unsophisticated to discern a “message” in a psychedelic experience or to engage with visionary entities as though they possessed their own sui generis ontological autonomy. I’m merely pointing out that this is one way of engaging with the phenomenon. And if you don’t see this, if you ignore the interpretive choice you are making, then you (a) render other interpretations inaccessible, and more importantly, (b) limit yourself to explanations that never allow the Other to truly disrupt your categories.

Which, it needs to be said, is the whole point. Hermeneutics isn’t a head game. The idea is to empower your encounter with otherness. By becoming aware of the hermeneutic dimension, by knowing your context, your interpretive choices, your projections, you are better able to discern when something is trying to puncture through.

McKenna holds his interpretations lightly, yes. But that’s not enough. He is still, at bottom, interested in a hermeneutical conclusion. He’s asking, What is “actually” going on? His interpretations are after a final explanation based on evidence, something that is “correct,” and as such still playing the game at the level of correspondence metaphysics. He uses aliens, gods, fairies, and other higher entities to explain the communicative power of mushrooms. Accordingly, our idea of reality as we know it isn’t challenged. We arrive at no new ontology.

And against the high strangeness of such psychedelic experiences as his—is that satisfying?

Psychedelic messages and entities exist in a profoundly unique and unfamiliar mode. McKenna senses that. It’s the reason, I think, his language is so rich and ecstatic. But it doesn’t matter how inventive you get with your adjectives. It doesn’t matter what fantastical hypertrophy of speculations you conjure. You’re still just hopping from one literalism to the next.

In True Hallucinations, the hermeneutic through which the McKenna brothers engaged with the whole experiment at La Chorrera rarely becomes an object of attention in itself. As a consequence, they never learn to leverage what is perhaps the most interesting, empowering, and mysterious dynamic of the whole story—the participatory dimension of all psychedelic exploration.

And just as with messages, so with maps…

Mapping Hyperspace

“Dennis and I, through a staggered description of our visions, noticed a similarity of content that seemed to suggest a telepathic phenomenon or some sort of simultaneous perception of the same invisible landscape.”

—Terrence McKenna, True Hallucinations

In his book LSD and the Mind of the Universe, Christopher Bache describes a harrowing experiment involving seventy-three sessions of 300-700 µg of LSD over two decades. He develops a nomenclature to help himself navigate the many extraordinary states he encounters through the years, and toward the end he begings to enter the most extraordinary of them all: “Diamond Luminosity.”

I was so taken by his story that, in early 2022, I organized an event in Brooklyn and invited Bache to join us via Zoom. At that gathering, a woman who had sat with ayahuasca a few times claimed in earnest that she, too, had experienced Diamond Luminosity.

I couldn’t believe the gall.

Like, you realize this dude took twenty years to get there, right? Twenty years of arduous narrativizing that, through exquisite attention and careful interpretation, gradually gave rise to what is surely but one out of a near-infinite set of possibilities inherent in consciousness—and which Bache named, in itself a hermeneutical act, Diamond Luminosity?

Right?

I get it. We’re social beings. We burn with the need to have our experiences witnessed and validated. Psychedelics in particular seem to trigger this need, partly because the wider culture is so illiterate when it comes to non-ordinary consciousness.4 But the temptation to legitimize psychedelic experiences by locating them on an objective map, a new “consensus reality,” isn’t the answer. It’s a new trap. Because what happens very quickly is the ol’ merging of map and territory: we collapse our representations with reality and, in a pyrrhic victory, trap ourselves in representations.

In other words, we lose touch with the inherent multiplicity and interpretive pluripotency of psychedelic experiences and get… literalism.

It’s not hard to find examples of this. On a podcast, I heard some dude who’d written a book on DMT describe the thought he had after his first trip: Holy shit, Alex Gray was painting a real place! I’ve heard similar things at the local psychedelic society’s Trip Tales. But most blatant of all is the Hyperspace Lexicon, a kind of OED for DMT states where you can find entries on The Waiting Room, Soul Surgery and the Hyperslap, as well as various common entities like the Jesters and the Mother Goddess.

Don’t get me wrong. When I discovered this lexicon a few years ago, I was thrilled; it was genuinely cool to see people taking seriously the challenge of mapping this crazy phenomenon.

At the same time, it makes me cringe to imagine the next generation of DMT-nauts coming down from breakthrough hits and, all starry eyed with metaphysical awe, gasping, “I saw them. I saw the Jesters!”

Rick Strassman himself, hero of psychedelic research in the dark ages of the 90s, edges toward literalism. At the end of his well-known book The Spirit Molecule, he earnestly suggests researching “the being-contact phenomenon and its relationship to parallel universes and dark matter.” Then, detailing protocols for a hypothetical future research center, he says: “it’s helpful to know something about current theories regarding ‘invisible realms,’ like dark matter and parallel universes. Equipped with these types of training and experience, research scientists and staff will be ready to understand, accept, and react to nearly everything that might come up during deep psychedelic sessions.” Unfortunately, by “accept,” I think he may be saying just what he means.5

Patrick Harpur, in his book The Philosopher’s Secret Fire: A History of the Imagination, has this to say to anyone describing psychic material as though it were “located” somewhere in the multiverse.

The whole debate about whether the unconscious is inside us or outside is a distraction… The unconscious, soul, imagination—whatever model we use—are in themselves non-spatial, just as they are timeless… But in order to discuss them at all we find ourselves falling back on spatial metaphors, calling the unconscious for instance an ‘inner realm’ or ‘an alien country outside the ego.’ But the unconscious is not a literal place. Images are not contained in it; images are the unconscious—‘image is “psyche,”’ said Jung... The unconscious is itself an image.

It’s tempting to act as if psychedelics bring us into some kind of shared navigable space. I mean, wouldn’t it be cool if, by smoking DMT, we could in fact adventure into a hidden parallel world? I think most DMT-nauts aware that this is a metaphor for what’s happening, at least at some level. But narratives ossify. It’s easier to describe your breakthrough journey this way. It’s easier (returning to the topic of messages) just to say, Ayahuasca gave me this idea, Shrooms told me that. It might even feel more socially meaningful.

So we cast aside the whole complex phenomenology that orchestrated the Aha moment, and just keep the Aha.

Fine. But isn’t it better to be self-aware about it?

Stop Reducing Me, Valve: On “Psychedelic Ideas”

“A psychedelic trip should not mean but be.”

—Andy Mitchell, Ten Trips

Such simplification also happens at a broad cultural level. Psychedelia is full of founding myths, origin stories, and ideas that people claim were inspired by psychedelics.

Example 1. Take Aldous Huxley’s notion of the “Reducing Valve.” Anyone who’s read The Doors of Perception probably recalls the book’s big epiphany: the brain, rather than producing consciousness, in fact constricts it from the unbounded “Mind at Large” down to a biologically useful trickle of data.

I used to think that this was one of those “psychedelic ideas.” But as Mike Jay points out in Mescaline, Huxley “conceived it as an explanation for the effects of mescaline some time before he took it: he had outlined it in his first letter to Osmond a month previously.”

(In fact, C. D. Broad, who Huxley credits with suggesting that the brain is “eliminative and not productive,” took inspiration from Henri Bergson. And if you want to dive deeper still, Bergson himself likely took inspiration from Nietzsche, who was onto this whole thing back in 1885: “…we have senses for only a selection of perceptions — those with which we have to concern ourselves in order to preserve ourselves. Consciousness is present only to the extent that consciousness is useful.”6)

In short, to credit psychedelics themselves with ideas is psychedelic literalism.

Example 2. Reading an essay titled “The Return of the Philosophy of Psychedelics (And Why It Matters)” I came across the idea that Plato owed his philosophy to a psychedelic experience:

It doesn’t seem so far-fetched to imagine a psychedelic origin of Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’: transcending the illusory sensory impressions of the material world (portrayed as shadows cast on a cave wall by a fire) and gaining knowledge of ultimate reality... “Whitehead famously said, ‘Western philosophy is a series of footnotes to Plato.’ If Plato was inspired by psychedelics, then the whole of the Western canon is unwittingly inspired by these experiences,” Sjöstedt-Hughes adds.

Plato did claim to be inspired by the Eleusinian Mysteries. And as we’ve seen, the Mysteries may have involved a psychedelic. But to present this as a linear story of cause-and-effect is sophistical. As we’ve also seen, the so-called messages don’t emerge ex nihilo. They arise from a rich froth of preexistent emotional and conceptual material. In this sense, the psychedelic experience in fact owes everything to us—to the cultural and personal context into which we plug Grof’s ol’ nonspecific amplifier. We could just as well say that philosophy (i.e. the myths and values instantiated by the Mysteries) inspired Plato’s trip.

Sixty years ago, Timothy Leary called this the “programmability” of psychedelic experience. Today, anthropologist David Dupuis puts it in less sexy terms:

Rather than opting for a seductive but angelic approach seeing psychedelics as substances capable of healing the world… psychedelics should be thought less as tools for social transformation than as vectors of cultural transmission. (Emphasis mine)

Example 3. Not because we need it, just because it annoys me. In that same essay on philosophy and psychedelics, I came across the sentence: “Huxley adopted a belief in the ‘perennial philosophy’ (philosophia perennis), inspired by psychedelics.”

Again! That cause-and-effect framing! But this time, I can prove it’s garbage. Sit down, hold onto your butts, and look at the publication dates:

The Perennial Philosophy: 1945

The Doors of Perception: 1954

Huxley took mescaline nearly a decade after formulating his ideas on perennialism.

What is going on here?

The overzealous impulse to locate psychedelic inspiration at the heart of Western thought and history drives no small number of books, blogs, and podcasts. Foucault in California, a charming but insubstantial memoir, has no raison d’etre other than the idea that Foucault, one of the Greats of 21st century philosophy, owed something to a psychedelic. Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes’ essay, “The Psychedelic Influence on Philosophy,” tracks the (very thin) engagement of philosophers with psychoactive compounds. And so on. Part of this, to be sure, is motivated by the desire to give credit where credit is due. It represents a search of truth in the scientific sense. But motivating that search is also a revisionist impulse, a need for academic and cultural legitimacy in the wake of drug prohibition and stigmatization. To put it crassly: we want to be able to say to those who judge us for our drug use: See? Plato did it!7

It’s a trauma response.

Haha… But seriously?

For my part, I’m not convinced that we need to enlist the authority of the ancients to justify our present-day investigations into consciousness. It’s nice that philosophy isn’t totally ridden with psychedelic virgins, and that, for example, William James huffed nitrous and understood Hegel better. But let’s not make too much of it. These simplified narratives will backfire, burying a hermeneutical dynamic that, were we instead to become conscious of it, would become for us a source of power and agency.

How so? It’s to this that we now turn…

*

At an event with the Brooklyn Psychedelic Society, author Rachel Harris told me that when westerners go down to the Amazon for ayahuasca ceremonies and, on the third or fourth ceremony, come to believe that the Mother Aya is telling them to be a shaman (a not uncommon event), what is really happening according to experienced Indigenous shamans is that they are misinterpreting the message. They are not being called to host their own ceremonies; they are being called to more serious ceremonial work for themselves.

The actual quote: “The universality of the hermeneutical perspective is all-encompassing.” Hans-Georg Gadamer, “Aesthetics and Hermeneutics,” 1977.

Dennis McKenna, Terence’s brother, confirms this literalistic framing in his own memoir, published many years later: “We believed an intelligent entity resided in the drug, or at least somehow communicated to us through it.” (Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss: My Life with Terence McKenna, 2012)

I mean, that’s why it’s called “non-ordinary.” If psychedelics were every truly integrated into the mainstream, becoming for western culture what they are to ayahuasca tribes in Peru, say, then we’d call it something less banal.

Strassman’s research participants leaned even more heavily in this direction. From page 195:

Josette said that some of what Jeremiah described reminded her of some of her own “weird” dreams, and she went on to tell us about one of them.

Jeremiah replied, That was a dream you described. This is real. It’s totally unexpected, quite constant and objective. One could interpret your looking at my pupils as being observed, and the tubes in my body as the tubes I’m seeing. But that is a metaphor, and this is not at all a metaphor. It’s an independent, constant reality.

Josette collected the last blood sample and left the room, closing the door behind her. Jeremiah and I relaxed quietly together.

DMT has shown me the reality that there is infinite variation on reality. There is the real possibility of adjacent dimensions. It may not be so simple as that there’s alien planets with their own societies. This is too proximal. It’s not like some kind of drug. It’s more like an experience of a new technology than a drug… It’s not a hallucination, but an observation.

From a notebook kept sometime between 1885–86 (Will to Power #505).

Just check out articles like this: https://qz.com/1051128/the-philosophical-argument-that-every-smart-person-should-do-psychedelics